Bruce Jewett Collection of Beatrice Wood Ceramics

Bruce Jewett Collection of Beatrice Wood Ceramics

The most recently added collection contains 25 pieces by the notable ceramist Beatrice Wood. The collection’s donor, Bruce Jewett, began purchasing the ceramics directly from the artist at her studio in Ojai, California in 1971, and continued to do so every year until 1991. These important ceramics were first exhibited at the Kellogg University Art Gallery in 1999 and prominently featured in various exhibitions over the decades.

About Beatrice Wood

“I owe it all to art books, chocolates, and young men,” Beatrice Wood would often tell those who made the pilgrimage to her Ojai, California studio before the artist passed away in 1998. There they’d find the fabled artist, in the last years of her life, swathed in a sari while working the potter’s wheel, and flanked by all manner of sacred objects: healing crystals, Hindu icons, and her signature opalescent vessels. For Wood, who lived to the age of 105 and made work up until her penultimate year, ‘art books, chocolates, and young men’ became the trifecta to which she attributed her longevity, and an abbreviation for the rich ingredients that made up her life. But the tagline, as her devout fan-base will tell you, doesn’t do Wood, or her work, justice.

Wood was a member of the New York Dada group and a pioneering sculptor. As a woman artist primarily working in ceramics, she also represented a demographic and a medium that were both marginalized during her lifetime. When discussing Wood’s legacy, more people tend to know her for sleeping with Duchamp than for making her own work. Wood met Marcel Duchamp in New York in 1916. Though a 1993 documentary later dubbed Wood the “Mama of Dada,” she is rarely listed among the movement’s pioneers –marginalized, ignored or erased– as were most women artists at the time. But in 1917, both she and Duchamp submitted works to the Society of Independent Artists’ first exhibition, which would double as Dada’s first public introduction. While Duchamp’s contribution to the show —a found urinal turned on its head titled Fountain (1917), which would later be seen as a watershed moment in the history of modern art— it was Wood’s Un peut (peu) d'eau dans du savon (A Little Water in Some Soap) (1917), that caused public uproar at the time. “She was…the sensation of the show,” explains Francis Naumann, a Dada scholar and dealer. “Her work was attacked by the press.” The offending painting showed a woman’s naked torso with a real piece of soap affixed “at a very tactical position,” Wood would later explain. She and Duchamp also founded the seminal Dada journal, The Blind Man, with artist Henri-Pierre Roché. In one issue, Wood penned an article defending Duchamp’s Fountain. “The only works of art America has given to the world are her plumbing and her bridges,” she mused, which is a comment often erroneously attributed to Duchamp himself. While Duchamp no doubt served as a mentor to Wood, her rebellious creativity didn’t start —or end— with him. “Beatrice was a romantic, but she never allowed a man to control her life —ever,” explains Naumann. “She paid her own bills from the very beginning to the end.”

Wood was born into a wealthy San Francisco family in 1893, but in her 20s she renounced their fortune, setting into motion a life of autonomy that was rare for women of her generation. She also distanced herself from Duchamp’s orbit as she grew to middle age. After her irreverent debut in the New York art scene, Wood eventually relocated to California, where she began making the shimmering ceramic vessels and satirical figurative sculptures that she’s become known for.

Wood started using clay, somewhat haphazardly, at the age of 40. Spurred by a desire to create a teapot to match a set of plates she owned, she enlisted in a pottery course at Hollywood High School, then went on to apprentice with ceramicists Gertrud and Otto Natzler. Wood was soon applying her signature panache to the medium, forging vessels and chalices jeweled with hand-hewn details --little blobs of clay arranged into intricate, uneven patterns; naked figures pared down to silhouettes-- and coated in glazes that give the effect of churning crystal balls. Her work was considered very basic and very exotic at the same time. “She was also taking a somewhat Persian aesthetic and glaze technology at a time when the information that American potters were pulling from was primarily from Japan. She was just on her own path.”

The famed Ojai potter Beatrice Wood is the primary focus of the Bruce Jewett Ceramic Collection. Twenty-five of her lustrous ceramics are featured in this collection, along with photographs of the artist, and her hand-made book.

More about the Donor

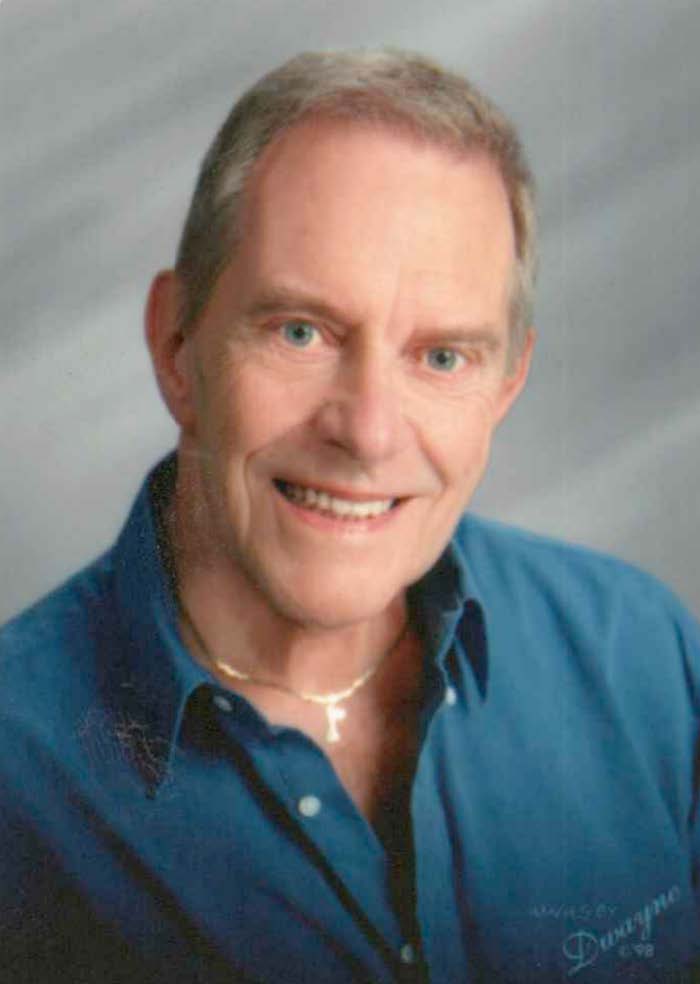

More about the donor, Bruce M Jewett: Kellogg University Art Gallery's annual competitive exhibition of ceramics, prints and drawings, known as Ink & Clay is made possible through sponsorship by the W. Keith and Janet Kellogg University Art Gallery of Cal Poly Pomona, and is underwritten by the generosity of Mr. Bruce M. Jewett and the late Col. James "Jim" H. Jones, and the Office of the University President.

Bruce Jewett’s generous support has been essential to the running of Ink & Clay each year. His contributions, as well as the endowments set up by himself and the late great Col. James Jones, make this campus tradition happen. “It is very important to support the arts,” Jewett often said. “Anything students can do outside of their specific major makes them a broader person.” Bruce Jewett always felt at home when he was at Cal Poly Pomona, especially when it’s time for the annual Ink & Clay art exhibition.

His partner, the late Lt. Col. James “Jim” H. Jones (alum from class of 1951, citrus fruit production), funded an endowment in 1971 for the initial Ink & Clay exhibitions. Jones was a U.S. Air Force officer who was stationed at posts across the Middle East during the Cold War. “Every time Jim changed stations, he would buy some new art to decorate his quarters,” Jewett commented. “When he changed stations on several tours, he would take all the [previously purchased] artwork to Cal Poly Pomona, and started a collection.”

Jewett’s own passion for art blossomed through association. “I hadn’t really been into visual art until sort of by osmosis from Jim’s interest and activities,” recalls Jewett, who also is a devotee of the performing arts. Jewett witnessed the exhibition grow from a small show of works by art department faculty members to a regional showcase to a juried competition that attracts artists from across the nation. He began providing support to the exhibition after witnessing the passion of those who have made the show a success year after year. “I was really impressed by the staff and faculty. Everyone seemed to be enjoying their job,” says Jewett. “The whole atmosphere at Cal Poly Pomona is like a family. They enjoy what they are doing.” Affirming his belief in the university, Jewett issued his bequest to Cal Poly Pomona. He gave annually to Ink & Clay for the James H. Jones Memorial Purchase for the exhibition, and supported other art-related programs in the College of Environmental Design.

Born in Highland Park, Michigan in 1928 as the only child of Merle and Edna Jewett, Bruce Jewett's introduction to the arts was as a saxophone student while in elementary school and his passion for the arts continued throughout his life. While pursuing his degree in Nuclear Physics from the Georgia Institute of Technology (Class of 1950), Jewett played his tenor saxophone in the marching band and was active in student drama group, Drama Tech where he performed in several productions. Among his professional accomplishments was his role as a civilian contractor for the United States Navy at Pearl Harbor for eight years in the 1950s and 1960s where he was part of developing nuclear powered submarines.

After his retirement from the professional world, Jewett was a docent with the San Francisco Opera and appeared as a supernumerary in several of their productions. Upon moving to Southern California Bruce played in the band at Irvine Valley College where he was later recognized for his contributions to their programs. Until his "retirement" from performing live music at age 88, Bruce played for the Desert Winds Orchestra where he also served as treasurer.

Bruce Merle Jewett was preceded in death by his partner, Col. James “Jim” Jones and is survived by his three daughters, Sharon Behm, Marilyn Jewett and Lisa Little; four grandchildren, Heidi Pettigrew, Kristen Welch, Hillary Jewett, and Nate Jewett; and seven great-grandchildren.

Bruce Jewett passed on June 21, 2020 and will be sorely missed. Upon his passing, Bruce Jewett had generously and preemptively secured a trust with the university with funds to support the Ink & Clay Endowment, the annual Col. James Jones Memorial Award, and his Beatrice Wood Ceramics Collection.