California Institution for Women

This case study was part of the Spring 2023 CHILE Studio.

CPP MLA Student Team: Chip Erwin, Megan Lassen, Tony Olea, Julian Ordaz Fernandez, Tessa Wiley

Image Credits: Julian Ordaz Fernandez, Tessa Wiley

The California Institution for Women (CIW) is a state women’s prison located in Chino, thirty miles east of Los Angeles in the southwestern corner of Riverside County. Originally founded in Tehachapi to the north, the prison moved to Chino following the Kern County Earthquake in 1952 and was rebuilt around a central yard, inspired by the progressive ideals and university campuses of the era. The site lies in the Lower Chino Creek Watershed, surrounded by the natural beauty of Chino Hills State Park and acres of farmland. However, the area is undergoing significant change, transitioning to residential & commercial uses, from dairy farms to million-dollar homes. That includes a planned housing development directly across the street from the CIW. The location is highly vulnerable to urban heat island effects and is the third-most impacted out of the thirty-three facilities managed by the California Department of Corrections & Rehabilitation (CDCR). It’s also disconnected from Chino’s water infrastructure, relying instead on resources from the California Institution for Men, six miles to the northwest.

The CIW currently houses over one thousand incarcerated female and non-binary people and employs a nearly equal number of staff. Each group has specific needs (and restrictions), but they share many of the same spaces. The staff noted that the prison system’s population is in decline. The incarcerated people who remain are part of an aging long-term population and require more health services. The staff group, on the other hand, sees high rates of turnover, reflecting the stressful nature of the job. Support for both sides may be coming, as the governor recently proposed a “California model” transformation for its prisons, patterned after successful rehabilitation programs in Scandinavia.

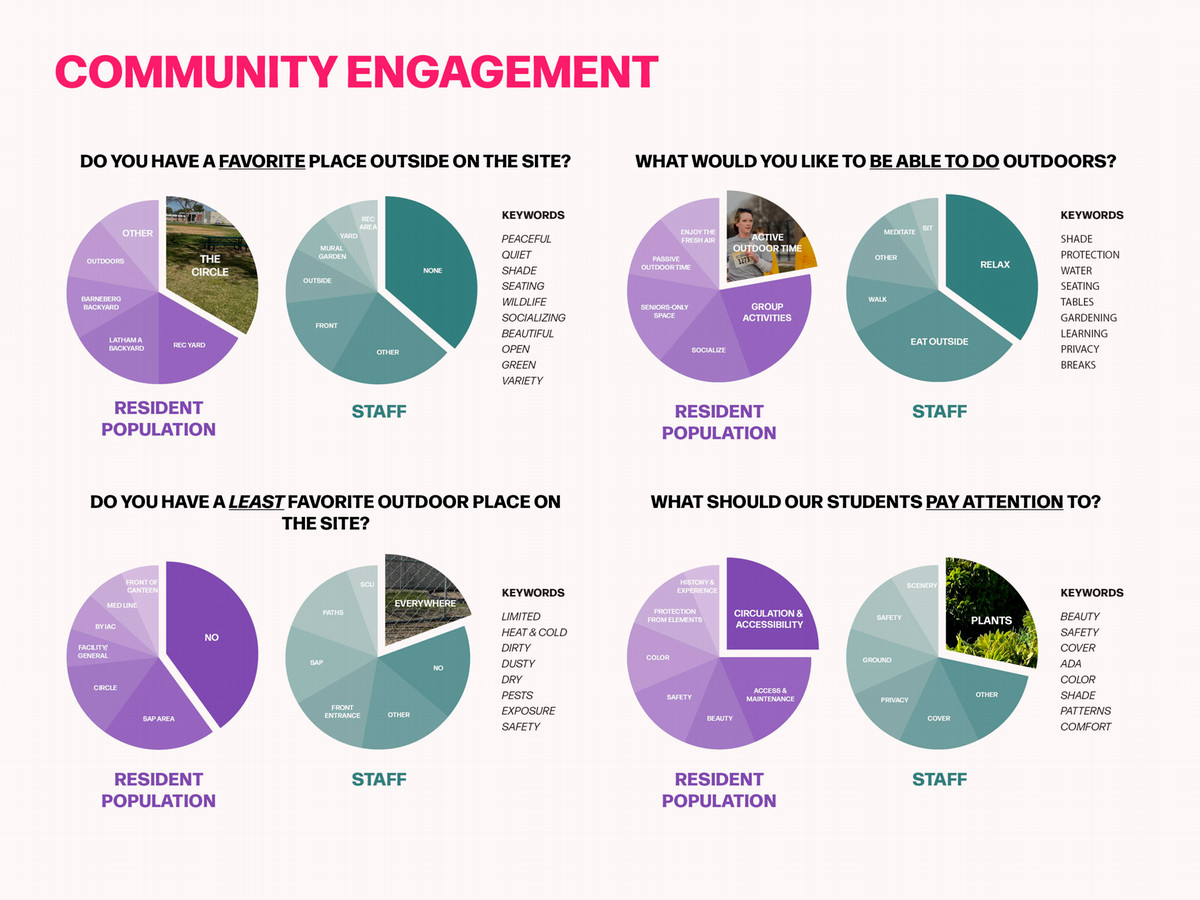

Our team’s community engagement plan was intended to generate a feedback loop of listening and learning between the resident women, CIW staff, and students. We drew on ideas from Design as Democracy, planning several meetings for the semester. These ideas were pared back significantly, as we acknowledged the limitations of time, distance to the site, and CDCR restrictions. But through distributed surveys, and meeting with a group of women already engaged by the non-profit Insight Garden Program, we were able to gather important feedback, and identify the community’s biggest needs.

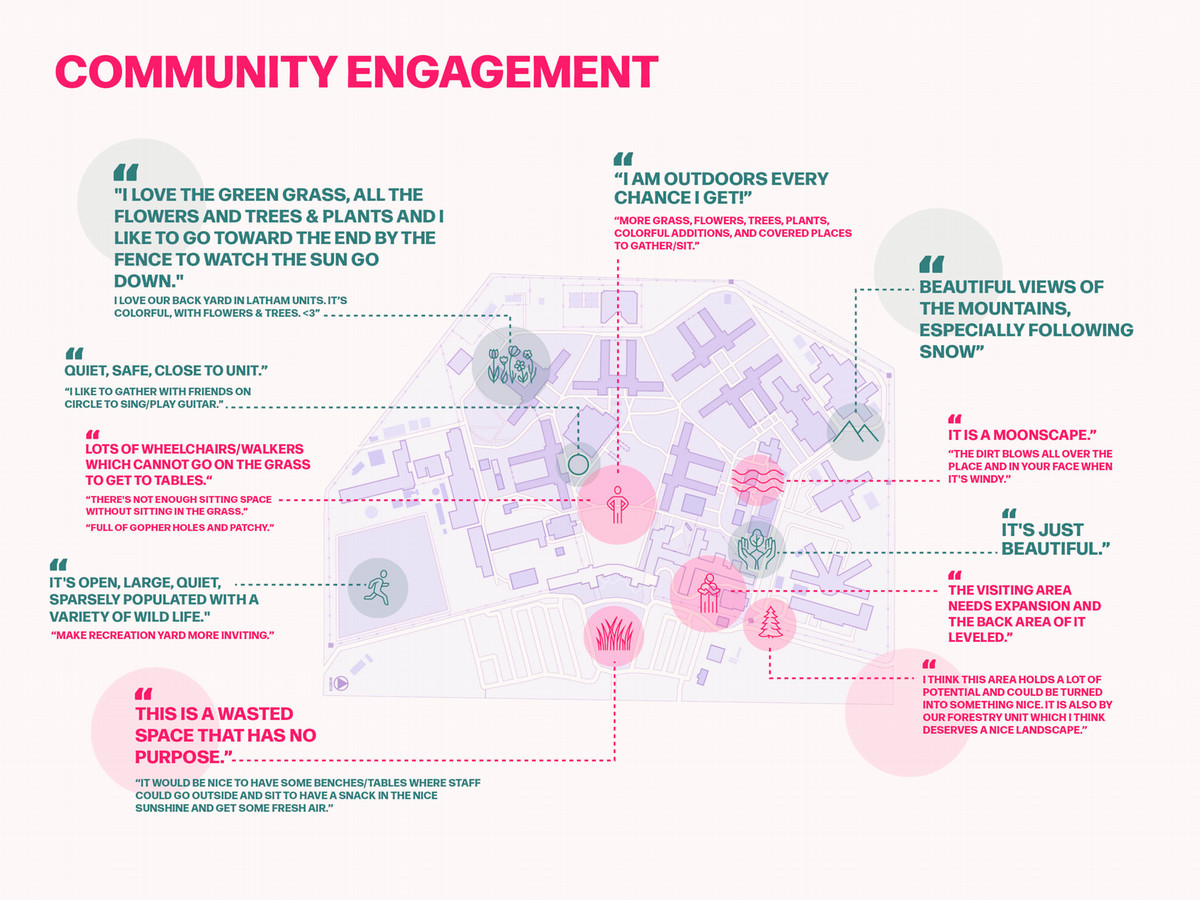

Surveys were distributed to staff and residents alike, with seventy respondents. The residents identified their favorite places as anywhere with peacefulness and shade, especially the few locations where small gardens had been allowed to flourish (as one survey put it, “I love our backyard”). They asked for spaces for outdoor activities, group socialization, and seniors-only areas, with special attention paid to accessibility. In contrast, the staff selected the entire site as their least favorite place and asked for places to relax and picnic while surrounded by plants. And although it was counterintuitive to our group as outsiders, the staff responses overall expressed empathy for the incarcerated, requesting environmental beauty and support on their behalf.

In addition to the surveys, the project team joined a meeting of resident members of the Insight Garden Program. Using a worksheet to help spark conversation, each student-led a small group in conversation about the site, learning more about the differences in feelings between age groups, and how residents navigated the prison system’s often labyrinthine rules as they went through their daily lives. The women here were a self-selected group of those expressing an existing interest in plants and ecology, and it became a chance for us to share with them. We talked about the field of landscape architecture and its potential to transform lives as well as the environment, offering a potential career path after incarceration.

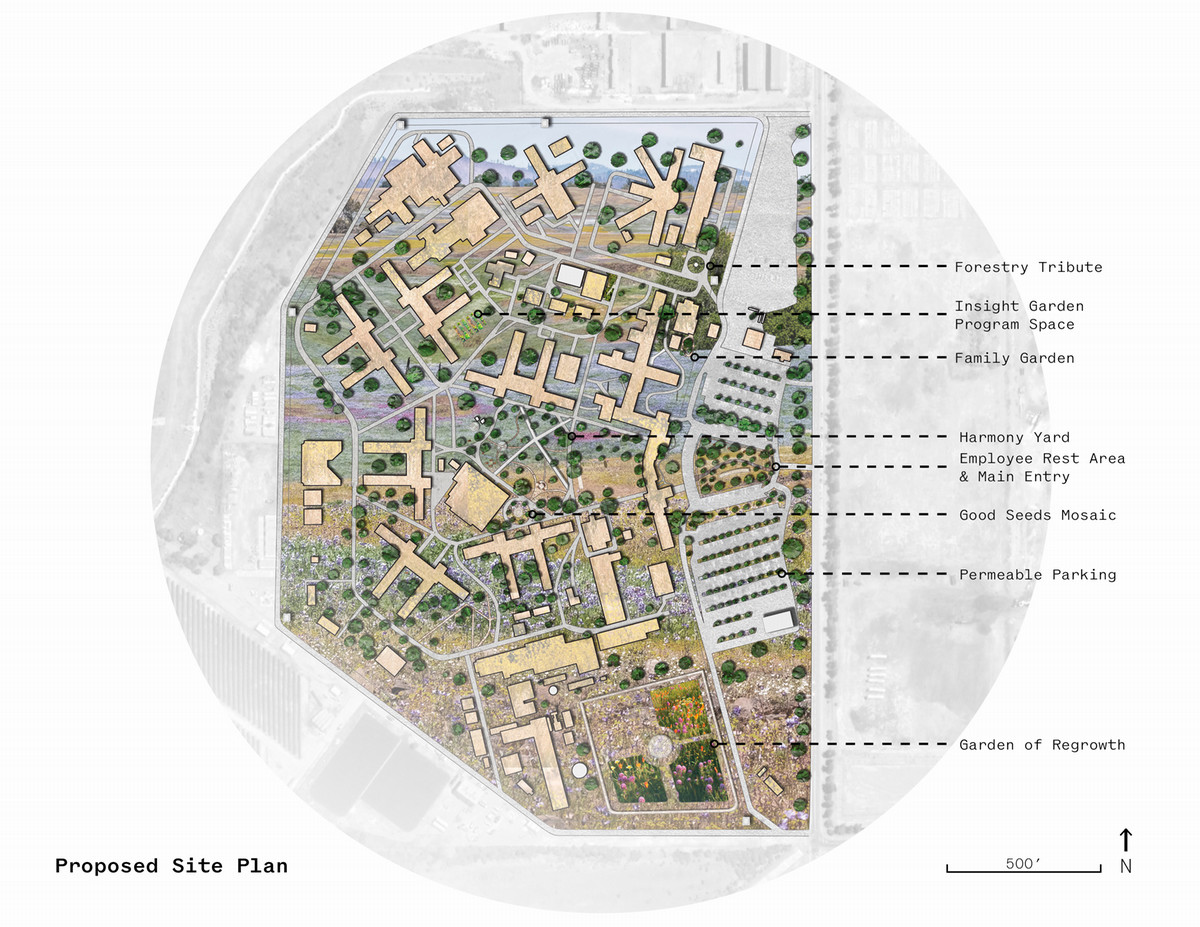

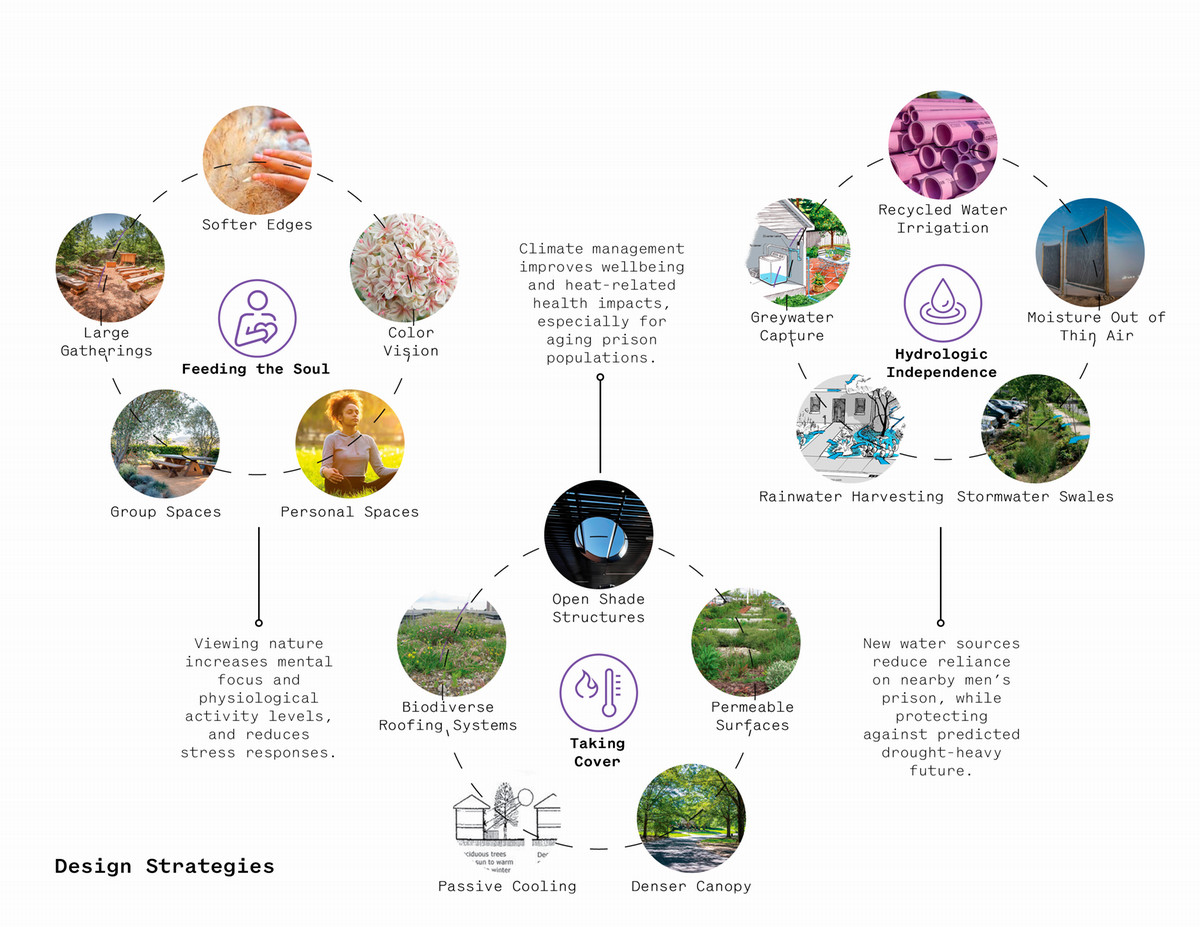

Through our engagement with the CIW community, we defined four key objectives. First, to create wildlife habitat and improve ecological conditions on the site, while alleviating climate change impacts and improving public health outcomes for the human inhabitants. Second, to find and develop opportunities for rainwater and greywater harvesting to increase the CIW’s hydrological independence and resiliency, while managing stormwater to prevent flooding in the rainy season. Third, to design in a human-positive way, using greenery and softened materials to support mental health and wellbeing, and art installations to inspire growth. And finally, to design for modularity, treating solutions as building components that could be tested and reconfigured as needed throughout the entire 120-acre campus.

A proposal package combining elements of each team member’s design approaches was approved by the CIW warden in March 2023 as a part of the California Model initiative, and the project is currently seeking funding.