Gaming in Higher Ed: Why Your Students Built Their University in Minecraft

Students across the nation spent hundreds of hours in a video game building their university at scale. Why?

By Christopher Park

The Minecraft phenomenon, essentially

In front of you is a burlap sack the size of half a sedan. Inside it is over a quarter-million Lego pieces—that’s enough to build a small town for a community of Lego-sized citizens. In the sack is a task scrawled on paper:

“Build this, at scale. Don’t forget the interiors.”

Flipping it over reveals the building in question—the marquee building in your university. With no further instructions, you dump the plastic contents on the floor.

How long will this take? 100? 200 hours? What about your unprecedented, all-virtual semester?

Irrelevant. You’re filled with determination.

This is the approximate headspace students are in when making this commitment in Minecraft, an immensely popular video game where you’re given the freedom to build whatever you want cube by cube.

So what’s going on here, and what can we learn from it?

What’s going on

Since COVID-19 robbed students of a full college experience, they’ve gone to build their universities in Minecraft. Google searches for “Minecraft server hosting” spiked in March 2020. Since then, Minecraft college campuses have sprung up—UCLA, Stanford, and Brown University to name a few.

These are herculean efforts with the guiding principles of accuracy and thoroughness. A single building can require over 250,000 cubes. Now add every building in your university—that’s millions of hand placed cubes. This isn’t limited to universities either, as elementary students in Japan have gone onto build elaborate recreations for virtual graduation ceremonies.

Further, these projects are done with few resources. Students search for floor plans and crawl the Internet for reference photos of their university. Once the idea forms and a plan takes shape, teams start their work on Minecraft maps—flat plains that stretch onto infinity.

“Once we set our minds to it and lost a little bit of sanity and time in the process, we were able to get quite a good look,” said one of our students.

Why it’s happening

Three things: love for video games, structure and accountability.

Students don’t need a reason to play video games—the hobby runs deep in their life. Gaming is predominately enjoyed by young people, but older generations aren’t far behind as they grew up with video games as well. Gender demographics also show that while males are the majority demographic, females make up a significant share. Zoom out further—approximately 244 million people in the U.S. play video games.

“They’re already doing this [creating in Minecraft] in the gaming space. They’re posting on Discord [a popular messaging app] at 2 a.m.” says Lily Gossage, Ph.D., director of Cal Poly Pomona’s College of Engineering Maximizing Engineering Potential (MEP) program.

MEP launched semester-long Minecraft competitions in the fall semester of 2019. The idea was put forth by her avid, Minecraft-playing sons. She floated the idea to the fall 2019 MEP cohort, and the response was an emphatic yes. Since then, student teams are tasked with recreating a Cal Poly Pomona building in Minecraft each semester.

|

|

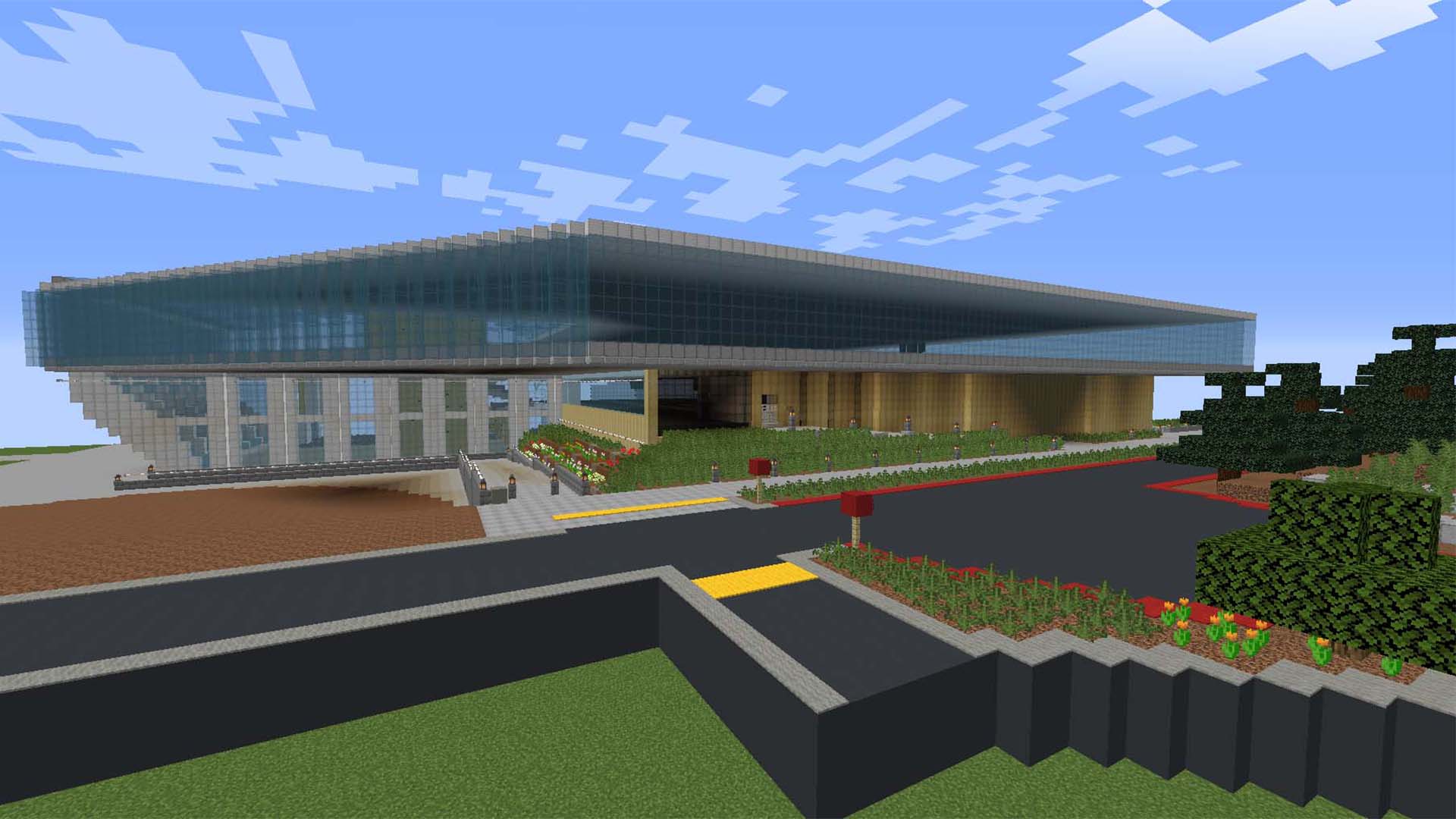

Left: Cal Poly Pomona's 165,000 square foot recreational and intramural complex built in Minecraft. Right: A recreation of a food court at Cal Poly Pomona. Both exteriors and interiors were painstakingly recreated by student teams.

Each team is restricted to three members and teams are required to provide weekly progress reports via screenshots of their in-development construction. Without these requirements, students fall behind, eventually abandoning their project, says Gossage. With the structure and accountability, the results speak for themselves.

What to takeaway from it

It builds communities. Students have been separated from their peers for nearly a year now. First-time freshmen have yet to take their first class on campus. Gaming brings them together.

“If they aren’t doing well in classes, they have an outlet,” says Gossage. “I’ve seen a couple of students who are typically withdrawn, but in-game they’re a totally different personality. It’s a way for them to meet other people.”

Students who took part in these competitions echoed a similar sentiment of social connection.

“Since we don’t have a bunch of contact with people now, there’s a big dent in our social lives,” says Stanley Rohrbacher, aerospace engineering student. “We found that playing videos games and going on Minecraft gave us a reason to all jump on the phone and talk for a few hours every night. It helps us maintain some of that social normality.”

“There is a whole area of brain learning, spatial motor skills, hand-eye coordination and critical thinking.” - Lily Gossage, Ph.D., director of Cal Poly Pomona's College of Engineering Maximizing Engineering Potential Program

It can engage, and sharpen skills. One study suggests that video games may be an effective engagement tool for nontraditional students—those who are older, have more responsibilities (i.e. work, family) and are returning to education after a pause. Another suggests that gamers were better on a number of cognitive skills than non-gamers.

However, literature is sparse. “This is a phenomenon that academia hasn’t had much of an interest in,” Gossage says, much to her chagrin. “There is a whole area of brain learning, spatial motor skills, hand-eye coordination and critical thinking.”